Simulating Fake Data in R

This blog post is on simulating fake data. I'm interested in creating synthetic versions of real datasets. For example if the data is too sensitive to be shared, or we only have summary statistics available (for example tables from a published research paper).

If we want to mimic an existing dataset, it is desirable to

- Make sure that the simulated variables have the proper data type and comparable distribution of values and

- correlations between the variables in the real dataset are taken into account.

In addition, it would be nice if such functionality is available in a standard R package. After reviewing several R packages that can simulate data, I picked the simstudy package as most promising to explore in more detail. simstudy is created by Keith Goldfeld from New York University.

In this blog post, I explain how simstudy is able to generate correlated variables, having either continuous or binary values. Along the way, we learn about fancy statistical slang such as copula's and tetrachoric correlations. It turns out there is a close connection with psychometrics, which we'll briefly discuss.

Let's start with correlated continuous variables.

# Loading required packages

library(simstudy)

library(data.table)

library(ggplot2)Simstudy in action

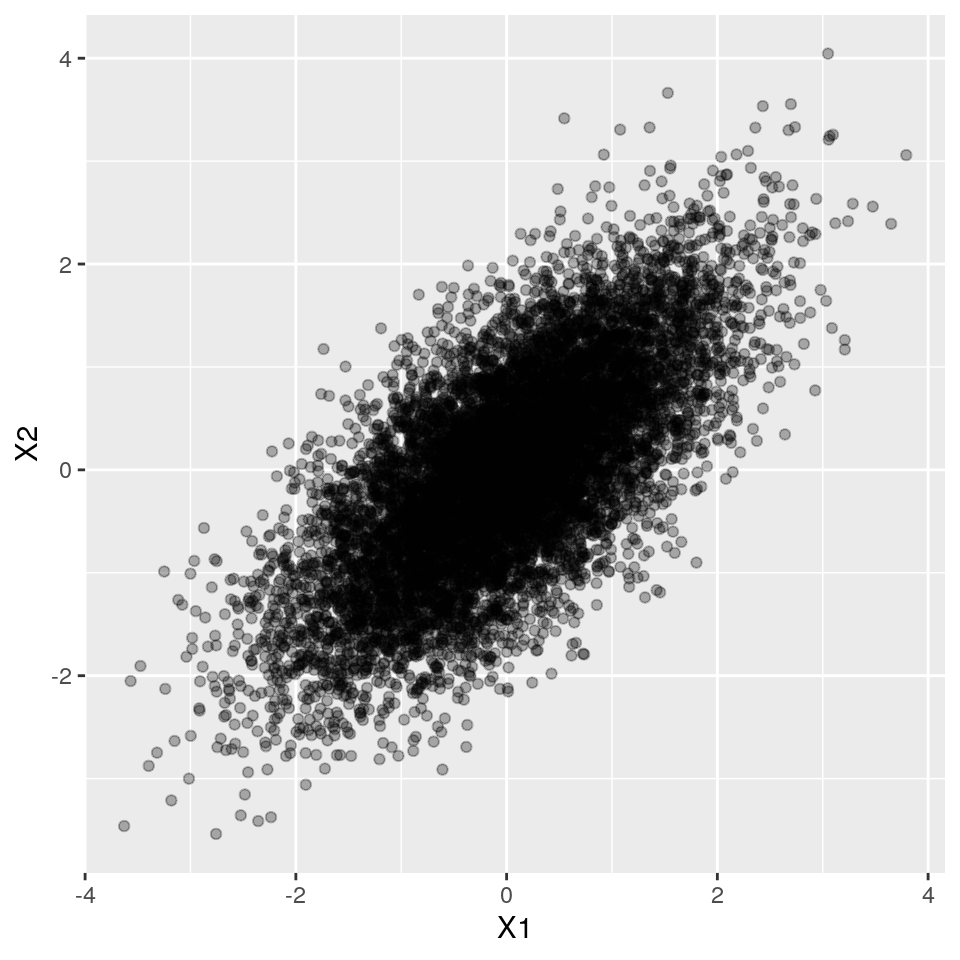

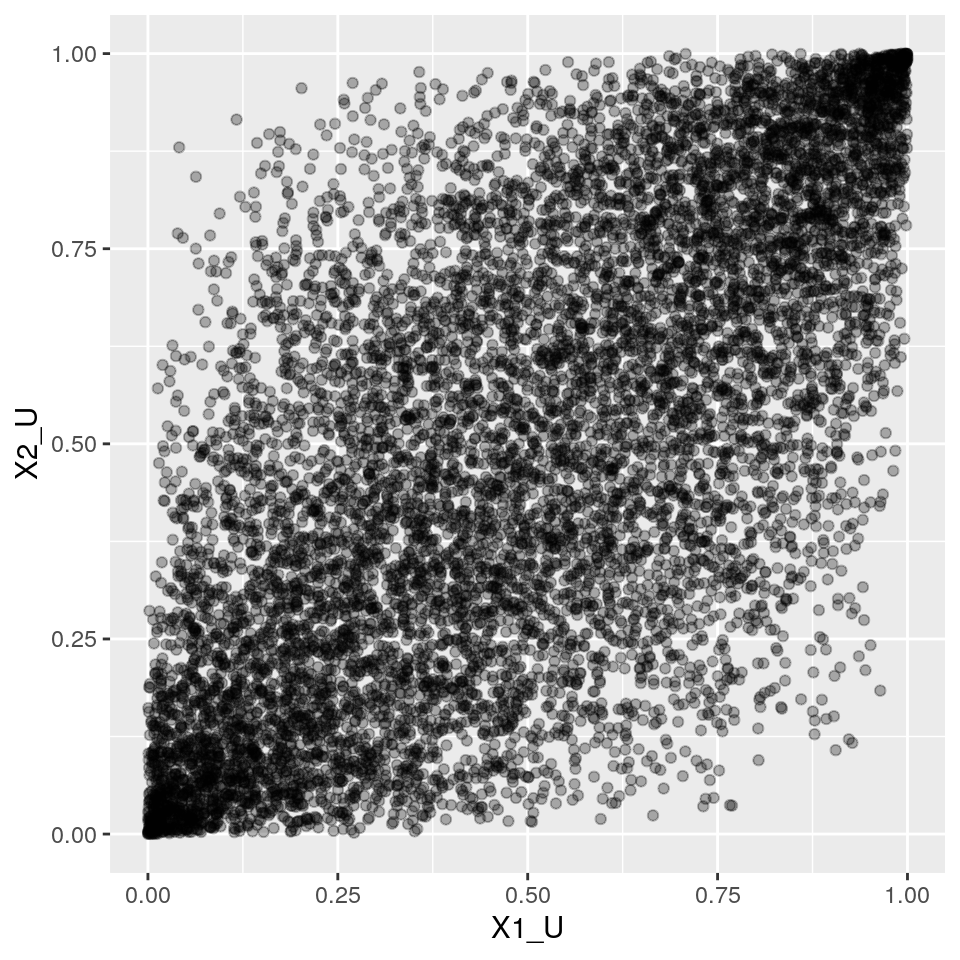

Now let's see how simstudy helps us generating this type of simulated data. Simstudy works with "definition tables" that allow us to specify, for each variable, which distribution and parameters to use, as well as the desired correlations between the variables.

After specifing a definition table, we can call one of its workhorse functions genCorFlex() to generate the data.

N.b. Simstudy uses different parameters for the Gamma distribution, compared to R's rgamma() function. Under water, it uses the gammaGetShapeRate() to transform the "mean" and "variance/ dispersion" to the more conventional "shape" and "rate" parameters.

set.seed(123)

corr <- 0.7

corr.mat <- matrix(c(1, corr,

corr, 1), nrow = 2)

# check that gamma parameters correspond to same shape and rate pars as used above

#simstudy::gammaGetShapeRate(mean = 4, dispersion = 0.25)

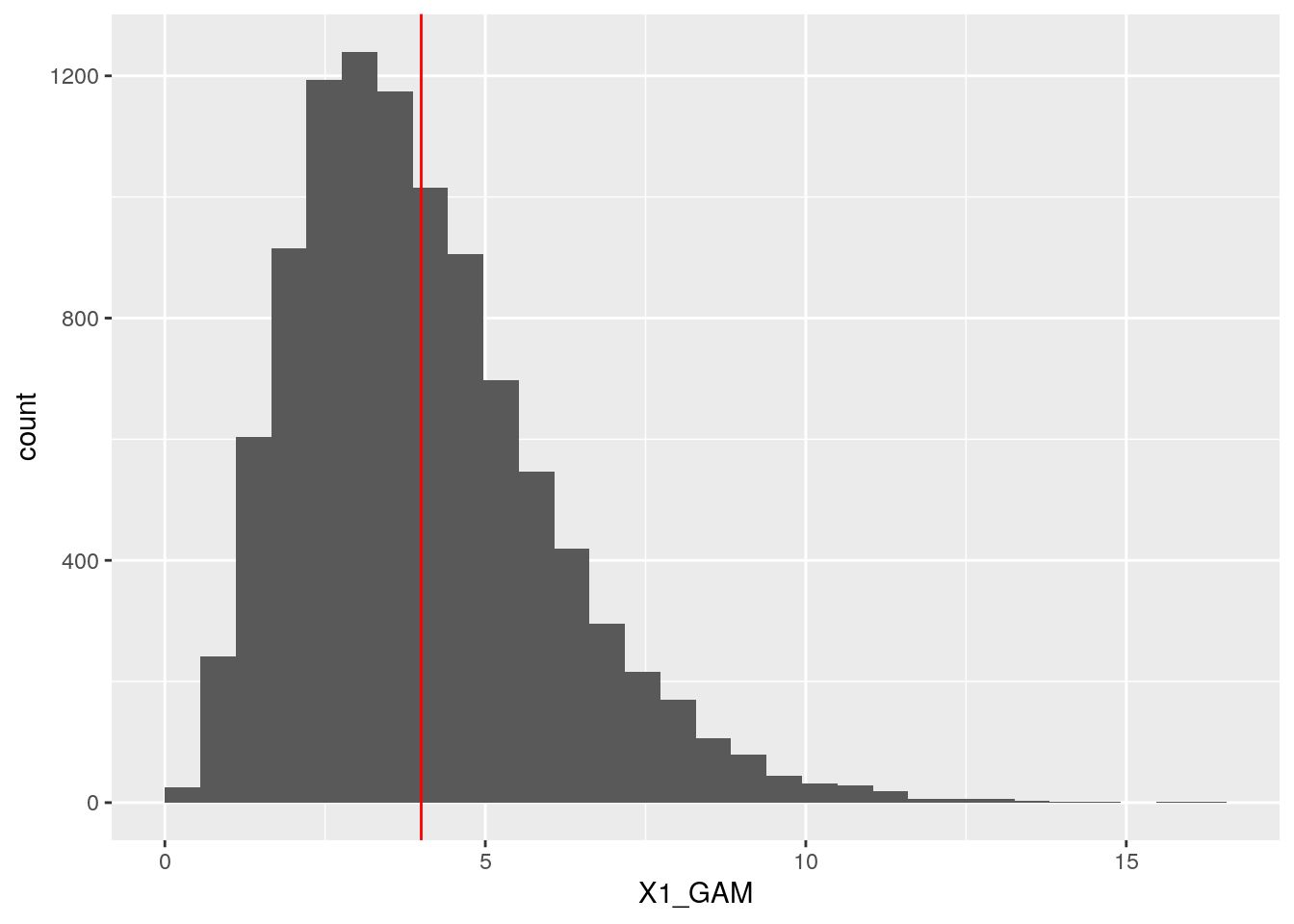

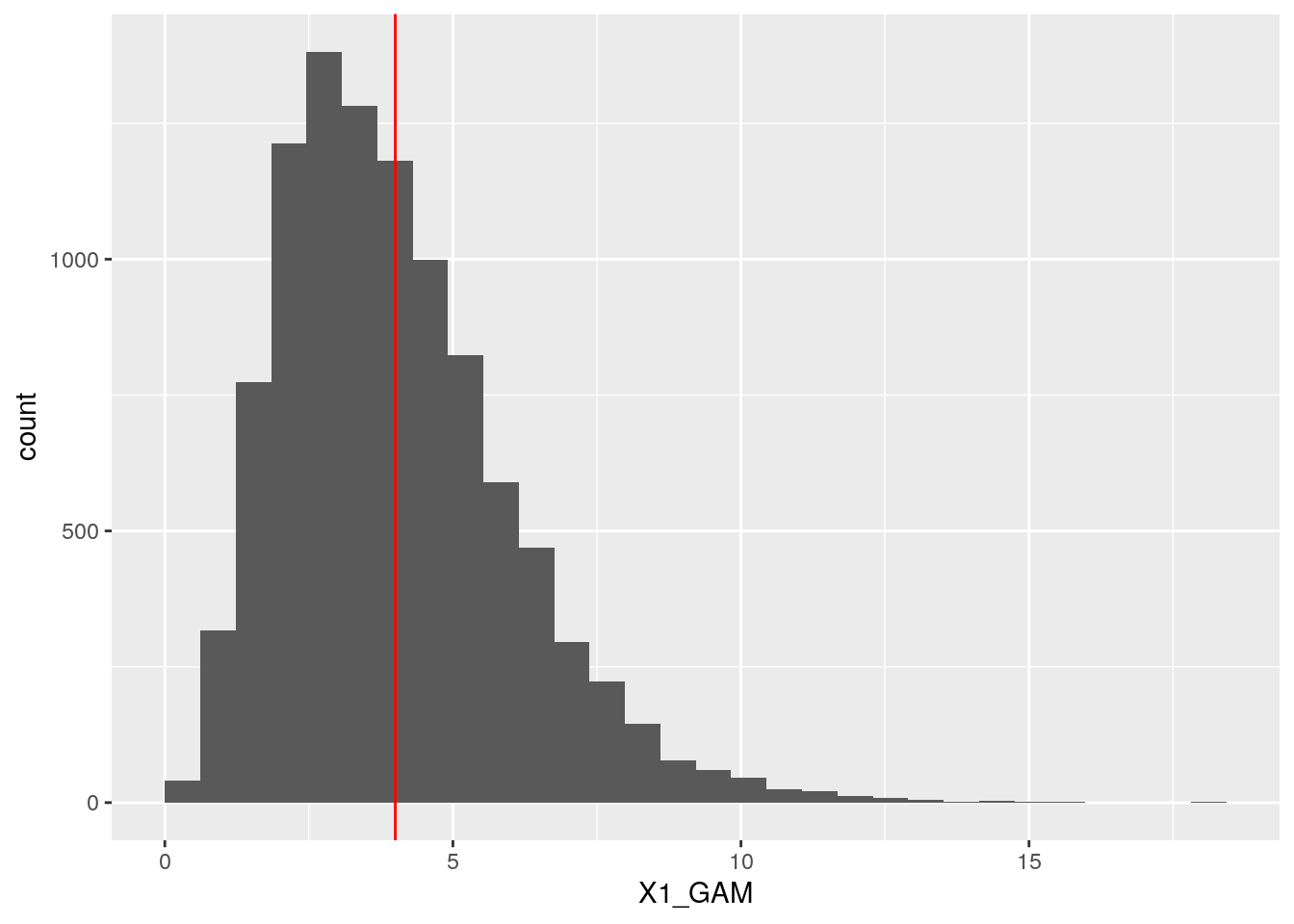

def <- defData(varname = "X1_GAM",

formula = 4, variance = 0.25, dist = "gamma")

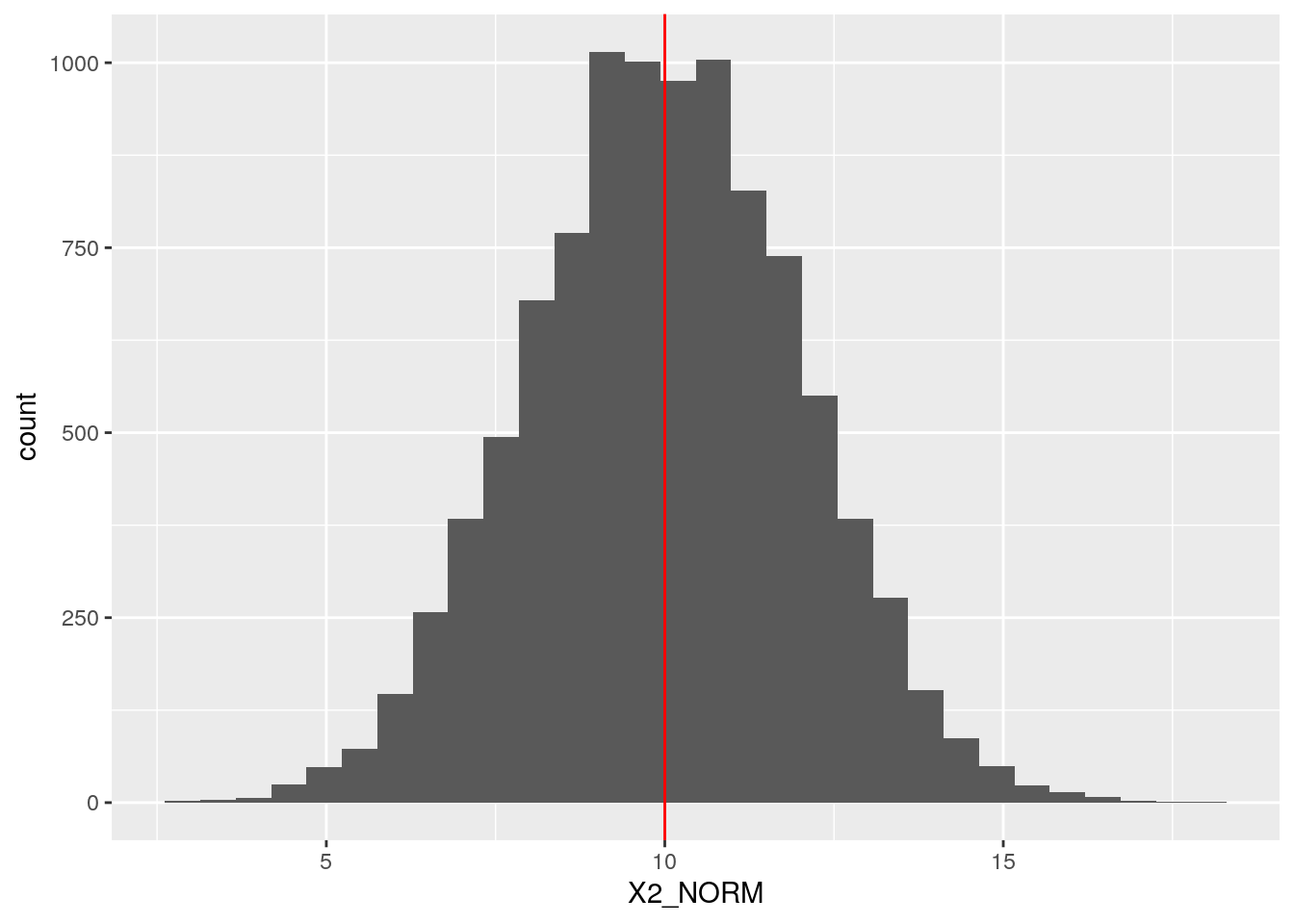

def <- defData(def, varname = "X2_NORM",

formula = 10, variance = 2, dist = "normal")

dt <- genCorFlex(1e4, def, corMatrix = corr.mat)

cor(dt[,-"id"])## X1_GAM X2_NORM

## X1_GAM 1.0000000 0.6823006

## X2_NORM 0.6823006 1.0000000ggplot(dt, aes(x = X1_GAM)) +

geom_histogram(boundary = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 4, col = "red")## `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

Relation to psychometrics

So what has psychometrics to do with all this simulation of correlated binary vector stuff?

Well, psychometrics is all about theorizing about unobserved, latent, imaginary "constructs", such as attitude, general intelligence or a personality trait. To measure these constructs, questionnaires are used. The questions are called items.

Now imagine a situation where we are interested in a particular construct, say general intelligence, and we design two questions to measure (hope to learn more about) the construct. Furthermore, assume that one question is more difficult than the other question. The answers to both questions can either be wrong or right.

We can model this by assuming that the (imaginary) variable "intelligence" of each respondent is located on a two-dimensional plane, with the distribution of the respondents determined by a bivariate normal distribution. Dividing this plane into four quadrants then gives us the measurable answers (right or wrong) to both questions. Learning the answers to both questions then gives us an approximate location of a respondent on our "intelligence" plane!

Phi, tetrachoric correlation and the psych package

Officially, the Pearson correlation between two binary vectors is called the Phi coefficient. This name was actually chosen by Karl Pearson himself.

The psych packages contains a set of convenient functions for calculating Phi coefficients from empirical two by two tables (of two binary vectors), and finding the corresponding Pearson coefficient for the 2d (latent) normal. This coefficient is called the tetrachoric correlation. Again a fine archaic slang word for again a basic concept.

library(psych)##

## Attaching package: 'psych'## The following objects are masked from 'package:ggplot2':

##

## %+%, alpha# convert simulated binary vectors B1 and B2 to 2x2 table

twobytwo <- table(df$B1, df$B2)/nrow(df)

phi(twobytwo, digits = 6)## [1] 0.099574cor(df$B1, df$B2)## [1] 0.09957392# both give the same resultWe can use phi2tetra to find the tetrachoric correlation that corresponds to the combination of a "Phi coefficient", i.e. the correlation between the two binary vectors, as well as their marginals. This is a wrapper that builds the two by two frequency table and then calls tetrachoric() . This in turn uses optimize (Maximum Likelihood method?) to find the tetrachoric correlation.

phi2tetra(0.1, c(0.2, 0.8))## [1] 0.2217801# compare with EP method

simstudy:::.findRhoBin(0.2, 0.8, 0.1)## [1] 0.2218018Comparing with the Emrich and Piedmonte method, we find that they give identical answers. Great, case closed!

Simstudy in action II

Now that we feel confident in our methods and assumptions, let's see simstudy in action.

Let's generate two binary variables, that have marginals of 20% and 80% respectively, and a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.1.

set.seed(123)

corr <- 0.1

corr.mat <- matrix(c(1, corr,

corr, 1), nrow = 2)

res <- simstudy::genCorGen(10000, nvars = 2,

params1 = c(0.2, 0.8),

corMatrix = corr.mat,

dist = "binary",

method = "ep", wide = TRUE)

# let's check the result

cor(res[, -c("id")])## V1 V2

## V1 1.00000000 0.09682531

## V2 0.09682531 1.00000000Awesome, it worked!

Conclusion

Recall, my motivation for simulating fake data with particular variable types and correlation structure is to mimic real datasets.

So are we there yet? Well, we made some progress. We now can handle correlated continuous data, as well as correlated binary data.

But we need to solve two more problems:

To simulate a particular dataset, we still need to determine for each variable its data type (binary or continuous), and if it's continuous, what is the most appropriate probability distribution (Normal, Gamma, Log-normal, etc).

we haven't properly solved correlation between dissimilar data types, e.g. a correlation between a continuous and a binary variable.

Judging from the literature (Amatya & Demirtas 2016) and packages such as SimMultiCorrData by Allison Fialkowski, these are both solved, and I only need to learn about them! So, to be continued.